.............................................................................................................................................................

the artist’s perspective:

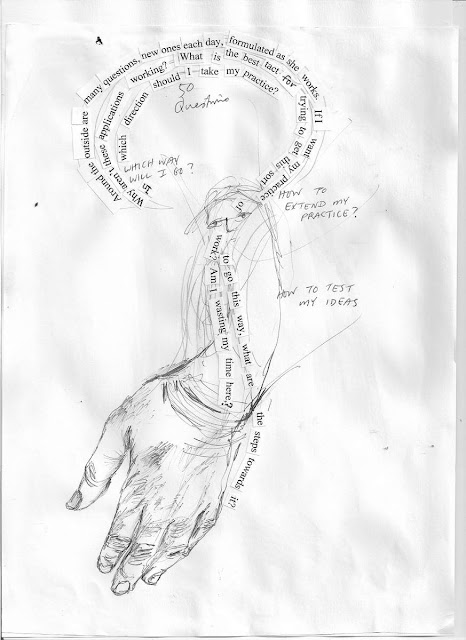

In the centre of this research, the artist’s practice and

experience sits heavily. It began before the research was imagined, the

research topic came from the artist’s practice and the artist’s practice will

most likely continue after the research is over. The artist's practice is

always an organic conglomeration of ideas, actions, physical materials,

physical processes, energy transformed into action and dialogue, all organised

within the limits of time which is metered out by the sun, and also influenced

by the needs of surrounding people (stakeholders) and the place of the artwork,

which tug the artwork this way and that. A little tug of war between what the

artist would do if she had no limits (the ideas that come into her head in the

early mornings), what she will do for money or what she will do to extend her

practice within the community, and doing what she thinks will get her more

work, more recognition or more pleasure and the constraints of the place and

materials and people involved with the work.

These are all intercepted by daily circumstances of family and life,

health and money, and the practical considerations when making public art. She

must rush off and buy chalkboard paint and organise the cement sheet. She must

unpack and pack the car amongst eating, house chores and a social life. The

physical self and the mental self also contribute or detract from the artwork.

Buzzing around the artwork process and its final outcome - the object, are the

ongoing effects of the physical world ready to intervene at whim. And then

there is the philosophical approach to the artwork, the why we do things –

which exist before it is even imagined, why the artist does what she does, how

our culture perceives community engagement in making artwork and how the

artwork exists afterwards in the world.

The history of my practice: I found some tiles in hard rubbish. I had a go at

mosaicking. But I was trained as a ceramicist. Clay. I thought, ‘Hang about,

could I put the mosaic in between the ceramics to make larger pictures?' I was

also a school teacher so I imagined how it would work with students. So I had a go at it with the art teacher at

my children’s school. We made a small 70 X 120cm triptych. The following year

they commissioned me to do a larger 20 square metre project. Then another

school got wind of it and so on and on it went and a practice and eventually a

business grew. Now it is the main way in which I earn my living.

Then

I became interested in how to use ceramics in public space as an individual art

practice. But when I first began doing it, I also had this feeling that I

needed to involve the people who lived and inhabited the area. I was practising

in their space. This is an ethical dilemma for me that has continued. But I

also alternatively thought that it was as justified as any other artwork in

public space which does not have the public’s permission. Most permanent public

artworks are not voted on by the community, and neither does advertising ask

its audience whether they would prefer it not be there. I was contributing to a

question raised 'Who gives you the right to put that in public space?" It

raised the issue that very few people have the legal right, but that organisations

with money or power have a greater ability to place their ideas and imagery in

public space.

There is something magical about it that makes people want to

be involved and makes people excited about the final work. They understand that

it might not be as beautiful or controlled as the work of the artist alone, but

that by including others in the making, it becomes something different and

something important.

When I make an artwork alone in public space, it is more of a

self-interested project and about my own ideas but when local inhabitants are

involved the artwork the ideas are more focused on communal knowledge,

understandings and experiences. It becomes a small but potent representation of

the surrounding culture.

Through the collaborative process the artwork is

bent and moulded by many people on its way to becoming the final static,

permanent object. The development of the artwork through the participation of

many people, is important for its growth and its ability to speak to people and

to speak about the culture and history of community and place.

What

is so good about artworks made by communities is that the authorship of them is

shared amongst many. Community members have the opportunity to make their mark

in public space and to be public artists. But along with this is the lessoning

of the artist as the author of the work. The artist becomes a technical

assistant, a leader, a guide, a facilitator and an artist working alongside

others. The authorship, pride and glory must be shared. The artist also has

less control over the artwork and what happens to it. They give over their

control in exchange for the participation of others. And they also often give

up ownership and sometimes authorship of the work. If they have exchanged their work for money,

they were hired and paid for their contribution. Sometimes their work will not

be known later as theirs. The artist may have to give up their ego and their

role as the creator in order to assist others to create.

Dichotomy

The process of community collaboration creates an interesting

dichotomy in that it can represent an individual in public space, individual

ideas, identity, choices, but also represents the community, collaboration,

compromise, negotiation, shared ideas and values, and, the working together

that produced the artwork.

You will have to allow for the ways other forces affect the

artwork - money, time, materials, place

of installation, the methods and materials needed for permanence and the

various needs and ideas of the other people involved, the expectations of the

commissioner, the wish to please the audience.

In a collaborative artwork all these things come together by chance and

effect the final artwork. It is organic in nature .

Permanence i.e. TIME

An object that exists over time generates lasting memories and ongoing thoughts. With permanent artworks the audience has longer to come to terms with the artwork and for it to burrow into their sub-consciousness and develop meaning for them. The artwork might become part of the identity of the place for them. Think about the average of 7 seconds that an individual artwork in a gallery might get from each person, in comparison with the repeated viewing of a public artwork that might sit in someone's suburb for many years - many people will come across it, have conversations about it, it will play a role in the community's life (whether loved or disliked) and it will become part of the place.

Often I don’t know how the artworks that I make with people

are responded to over time, how they become part of a place, I know very little

about how individuals and communities think about these artworks later down the

track. But I have experienced and been very moved by the way in which they do

become owned by the community. An example of this is once when I worked with

children to make an artwork which acknowledged the indigenous history of the

place, a mother with indigenous heritage offered to smoke it in. For me it was an instance of the artwork

becoming part of that community and the community embracing it as something

valuable.

Many

community engaged public artworks are ephemeral which means that the artwork is

temporary and not kept as an art object after the event or process. In these

works the emphasis is often on engagement and participation. Often, when I describe

my research topic, people tell me excitedly about a wonderful artwork they know

about, but it is often ephemeral and no longer exists. The difference between

permanent and ephemeral artworks is that they use time in different ways.

Permanent art, takes up more time and doesn’t generally deteriorate over time,

and its use of more time gives it a higher status. It exists over decades and

so it gathers meaning and becomes part of the place and the history of the

surrounding people.

I

tend to think of ephemeral as the opposite of permanent. Public artworks tend

to be either permanent or ephemeral but the division between them, where one

starts or the other ends is not clear. Permanent and ephemeral works can share

some aspects but could also be viewed as oppositional. A permanent artwork

generally is an object whereas ephemeral art has a greater emphasis on the

process and experience it provides. Here a little pattern develops where permanent

art is an object so it must be made with the physical outcome in mind, whereas

ephemeral and community art are in the process bucket but more than often also

have physical substance.

It is easier to achieve community engagement in ephemeral artworks whereas it’s much more difficult to get a commission for artworks with community engaged as makers because it makes the artwork unpredictable in all sorts of areas. Who wants to commission a permanent artwork without knowing what it will look like? We can think about the terms often used in public art policies such as - quality, well-known and reputable artist, significant, enhance - to realise that artwork by non-artists becomes problematic. There is more at stake when you make something permanent.

Ephemeral art is an event and is not expected to also be a valued object. Both are governed by time, but permanence is higher in a hierarchy of time. ( fig. ) Permanent public artworks are also valued for being made by artists of repute. In this instance the value and importance of the object increases, they become an object of value collectively owned by the people. They are also a burden for councils, in that they need to be maintained and kept clean and free of vandalism and not de-commissioned.

The artist’s role:

Have

I been herding People?

Why

am I doing this?

What

am I doing?

My role as the artist is about being someone who can move the

work from ideas to fruition and also having the experience of doing this. The

artworks that I have made in the past have to be shown, as photographs and they

are aesthetically judged by the potential commissioners. The artist has to

provide evidence of what they can make before being offered the job.

My job as an artist includes many things and it is mainly to

listen to the ideas that the community has and to pull these together into a

design and process that will create an artwork outcome that everyone will be

pleased with, but which is aesthetically pleasing, encompasses the ideas,

includes everybody as makers and will stand up to time and weather. I have to

marry the ideas of the project to a physical structure that can last over time.

The

role of the artist is expanded and includes communication, social skills, the

ability to assist people to work together and the ability to get along with

people. When operating in public one has to consider the audience. When you

leave the studio and enter the outside world, you need to respect that public

space belongs to everyone. It is not an extension of your own studio. The

movement of the art from a private space to a public space takes on a burden of

censorship, political correctness, the role of engaging and pleasing the

audience, being careful not to offend. The artists must develop relationships

that assist in the artwork’s process and outcome. You have to move it through

from the idea to the object, taking everyone on board the journey.

Hope and trust:

When people commission me

to make an artwork with them, they have to trust me and I also have to trust

them. We must undertake to work together and negotiate our ideas, roles and

responsibilities. Each decision has to be negotiated as we go. It is difficult

for anybody to imagine the final product. Even I cannot see it clearly. We must

launch together on a journey of interdependence. The community or commissioners might base their trust

on photographs of my past work. I always feel a bit of sorrow for the

participants as they make the ceramic work because they cannot see the bigger

picture and how it will look when complete. The participant does not understand

why they need to make it a certain thickness, why they need to smooth the

edges, why paint it in a particular way and how their own artwork will look after

firing. When making ceramics, the clay and the coloured paint will be a

different colour when it is complete, there is perhaps a sense of disbelief, a

walking out on a limb for the community participant. The underglaze colour ultramarine,

is lilac when you paint it onto the clay. I say, 'trust me, it will turn out

dark blue.' The participants make the work with the hope that it will be as the

artist says. They place their trust in the artist that their input will be

valued and used in the final artwork.

The

artist can take on many roles:

•

aesthetics control ( where the artist uses

different means to keep the artwork appealing)

•

quality control ( where the artist tries

to make sure the artwork is technically proficient and also of good quality.

They might do this by setting rules about how the artwork has to be made or

rules about what gets included in the final presentation).

•

keeping to plan - artworks are usually

organic things, so the artist can keep this organic process on track so that

the final result will appear to be what had been discussed. There might be some

leeway for the artwork to take on a life of its own, or there may be not.

•

keeping to the timeline

•

making everyone makes their artwork

successfully, and feel that they are part of the bigger artwork.

•

That the artwork is made in a way that

enhances the final artwork. That the participants do the best work they can,

that the edges are smooth, the right colours used.

•

Ensuring the work will be physically able

to be incorporated into the larger piece.

•

Making sure the individual contributions

of participants fits in with the collaborative plan.

Why we make it

My agenda is related to the idea of a democracy of voices in public space. It plays with the idea of community members participating and contributing to public space and expressing culture in public space, and providing an 'other' voice besides that of advertising.

I have different reasons for making the artwork than those of the community that I make it with. Each person has their own ideas about why they are doing it. Many commissions begin because there is something to commemorate and an interest in involving people in making as a part of this commemoration. The initial excuse to begin is often an anniversary, a year level that’s leaving the school, a problem area that needs beautification or the wish to create something to give colour to a dull place. But people are excited about the project and willing to put time and money into this art, for other reasons beside what provoked the project. They see art as a useful vehicle to explore or commemorate an idea as a community and they are excited about having artwork in their place.

My perspective comes from the experience of making many of these works. I am not the community that participated in and have the work in their place, I am instead the witness to what they gain from the process over and over again as I see what happens in a number of projects. I also imagine the potential of this community collaboration in other types of public places and in larger forms. I mainly work in schools. Schools are public places but they are also private in that not all of the public has access to the artwork.

And I am also interested in bringing art back to people. I think that people should participate in making art and that the art they've made should be in public space, that we should make our own mark on public space.

A closer Authenticity to place and community if made by community:

I have done many art-works in public space as a solo artist. Whilst these are very rewarding, they are solitary acts and rarely do I receive feedback from the audience of this work. Sometimes I feel like an intruder because it is not my local place. But when I work with people from the local community, and we make something together it means something much more. The artwork has to take on a life of its own out of the grasp of the artist. It is moved and altered by what the community does in the artwork. I feel that this gives it an authenticity of subject and place. I also hear and participate in the dialogue about the work. I hear the enthusiasm and joy and feedback about the work relayed by conversation, word of mouth, texts and emails. There is an excitement about the artwork and its relationship to the outside world that my own private art enterprises rarely find.

The magic of art, (which is the reason many people get enjoyment from it) depending on the person can be emotional or spiritual. Art has the ability to capture things unspoken and un-writable. People respond to art because it reflects and plays out a version of their lives in an abstract way. It might show you something that you have always suspected or known about but in a new way, that isn’t easily explained or described in words or text.

I have done many art-works in public space as a solo artist. Whilst these are very rewarding, they are solitary acts and rarely do I receive feedback from the audience of this work. Sometimes I feel like an intruder because it is not my local place. But when I work with people from the local community, and we make something together it means something much more. The artwork has to take on a life of its own out of the grasp of the artist. It is moved and altered by what the community does in the artwork. I feel that this gives it an authenticity of subject and place. I also hear and participate in the dialogue about the work. I hear the enthusiasm and joy and feedback about the work relayed by conversation, word of mouth, texts and emails. There is an excitement about the artwork and its relationship to the outside world that my own private art enterprises rarely find.

The magic of art, (which is the reason many people get enjoyment from it) depending on the person can be emotional or spiritual. Art has the ability to capture things unspoken and un-writable. People respond to art because it reflects and plays out a version of their lives in an abstract way. It might show you something that you have always suspected or known about but in a new way, that isn’t easily explained or described in words or text.

I also feel that creativity and art-making have been cut off from people. That making should be something that we can all do. My works seeks to bridge the gap between the creator and inhabitants of space.

I want to encourage people to think more broadly about making things in their own spaces.

Why can't we have more art in public space with ordinary people making the artwork?

I could attempt to answer these questions by writing, reading the literature written about it, or by an art practice that begs the question. I could ask the questions using public space.

Lawrence Weiner * suggests that if I put anything in public space, I will be asking a question.

This parallels my line of thinking, where I think that if I make a particular artwork in public space, then people will ask why is it there, who made it? Why did they take the trouble? questions are generated.

Actually placing the art object into public space creates a dialogue in the form of questions about why it is there and what its role is.

Lawrence Weiner * suggests that if I put anything in public space, I will be asking a question.

This parallels my line of thinking, where I think that if I make a particular artwork in public space, then people will ask why is it there, who made it? Why did they take the trouble? questions are generated.

Actually placing the art object into public space creates a dialogue in the form of questions about why it is there and what its role is.

* 'Art is one of those things that has no central definition, it has a history and it has no qualifications. It has no need of a reference point to anything else. Art is one of those things that appears in the world because somebody decides they're gonna pose the question and that makes it art.'

Lawrence Weiner, the means to answer questions, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AscU8wKzbbE

Lawrence Weiner, the means to answer questions, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AscU8wKzbbE

Why we make it? Cultural democracy, - everybody’s culture

I see public space as an increasingly controlled area, and I became interested in the individual’s ability to mark or alter public space. It had a great resonance for me, particularly when urban landscapes were visually dominated by architecture, official signage and advertising.

In one sense this authorized use of public

space prevents discrimination and slander and graffiti, but on the other hand

it gives the power to visually speak in public to those with money. It was illegal for individuals to make their

mark on society without authorisation. One of the consistent arguments of

graffiti is that they are questioning and challenging the ownership of space. I

saw community artworks as another way of challenging the situation and offering

other values and understandings of culture.

Billboard advertisements are not democratic. If you have a lot of money you can present your ideas by buying the right to public space in this way. When individual artists asserting their imagery in public space this is also undemocratic, but by doing so they raise the question about who has the right to place imagery I public space? We get this strange dichotomy of individual and community within public space, where the public has no power to insert into public space but when an individual does intervene it is in much the same undemocratic way. This is echoed in the dichotomy of community collaborations where each person contributes their own individual work but towards a larger group process and outcome. We get the individual within community and both are aspects of ‘public art’.

My thinking is that what you see in public space influences your thinking and affects how we learn and know things. Public space doesn’t reflect things such as gender equality, ethnic diversity, and other realities and histories. Advertising promotes ideas of homogeneity and what we should aspire to, with the main aim of persuading us to buy a certain brand or product. Individual voices and 'other' voices are not generally heard or seen in this space.

Art can be a very powerful medium when used in public space. Because it doesn't belong. It stands out. Particularly handmade art, stands out as something not functional and as not a building. It works against against our increasingly ordered, digital and technological environment.

obstacles, tensions difficulties, challenges

The brick wall or my perspective

In our culture there are different statuses

and categories for things and the artwork that you make with people doesn’t

fall into the category of permanent public art commission. I became

increasingly aware that my understanding of my practice and its importance and

its potential was not seen in the same way by others. They did not have this

same perspective about community participation in permanent public art. They

did not imagine community art as permanent public art. It was really important

to me that it be considered permanent public art, that it not be immediately

categorised and thrown into a different bucket called ‘community art’.

You

could say that my research began when I found a sort of invisible barrier to my

work. It was easy to get work in schools and they wanted this type of artwork

where everyone had made a part of it. People understood the idea and they

understood the meaning. They weren’t often worried about the aesthetics perhaps

because they had seen my previous work and trusted me but also because the idea

of everyone joining in was very important to them and they understood that you

had to let go of 'excellence', in order to have participation.

There

were a range of perspectives besides mine. The philosophies about permanent

public art and community art did not seem to overlap but instead sit in

distinctly separate buckets. As soon as

I mentioned the community were involved, the person I was speaking to said

"oh yeah community art". There seemed to be no support for a

perspective that encompassed both areas of practice. Small projects where

community members participated in making were got up everywhere in public space

and some of them permanent but they were usually small in size and budget. They

sat in places like parks and gardens, under the radar and not called permanent

public art.

Ownership,

acknowledgement and creative authorship

Who owns a public artwork where the community have been involved as makers? And who is acknowledged? In some of the recent artworks I have made, the first names of those involved have been installed into the artwork. But this raises the question of, 'why not the second names?' It is difficult to place the second names of participants, if they are children because of privacy rules and parental permission. Then whose full names do you include and whose do you not?

Often when I am making an artwork with students towards a permanent piece they are unhappy that their names are not included. They are used to writing their name on every piece of work they do, both drawn and written. The name is a traditional part of the maker’s stamp and people enjoy writing their names on their work and in primary school you have to write your name on every loose piece of paper. But I make a rule that no-ones name is on the work including my own. I become the facilitator, and unnamed. Then at other times particularly if it is a voluntary work i want to be acknowledged so I might add acknowledgements.

Who owns a public artwork where the community have been involved as makers? And who is acknowledged? In some of the recent artworks I have made, the first names of those involved have been installed into the artwork. But this raises the question of, 'why not the second names?' It is difficult to place the second names of participants, if they are children because of privacy rules and parental permission. Then whose full names do you include and whose do you not?

Often when I am making an artwork with students towards a permanent piece they are unhappy that their names are not included. They are used to writing their name on every piece of work they do, both drawn and written. The name is a traditional part of the maker’s stamp and people enjoy writing their names on their work and in primary school you have to write your name on every loose piece of paper. But I make a rule that no-ones name is on the work including my own. I become the facilitator, and unnamed. Then at other times particularly if it is a voluntary work i want to be acknowledged so I might add acknowledgements.

How to practice in public space?

One

method of developing you public art practice is to make your art illegally and

independently in public space. Studio practice can’t just slide outside and

onto a wall, public space has other things to consider. The practicalities of

materials, working within the site and audience reception, are a few of the

things that make it different from a studio art practice. And you learn better

learn by doing.

Because

I was aware of what you could and couldn’t do in public space, or what was

assumed you couldn’t do, I was interested in stretching the borders. It would

be like quietly pressing the wall sideways like in the Seinfeld episode where

the apartment walls moved as someone tried to make a bigger space for

themselves. So the wall is quietly moved

and then others notice that it can be moved. Or you sort of momentarily stretch

the rubbery hide of public art, out a little in once direction. When it flings

back into shape it has a forlorn altered look where you have stretched its

elastic. The dint is not the shape you made but it’s noticeable and it changes

the way that restriction looks. You’ve altered its taughtness, and people have

noticed that it does stretch.

I

wanted to apply for bigger council commissions but it was hard. Councils wanted

several things that I didn't have and which were difficult to get. For example

they wanted you to have experience at doing a project that had a similar budget

and have examples of work which was of the same size and style. There was this

strange issue of needing to have experience practising in public space where it

was difficult to get a commission without experience. It was a palindrome.

(drawings

of palindromatic snakes)

Perhaps

it was not only the money but this nagging idea of the potential of these large

budget projects to really do something interesting and to also get paid

properly. Now we can see this as an artist’s perspective and bad luck because

you don't have experience but what is tremendously important about this is that

it signifies a general issue that it is very difficult for artists to become

public artists. Architects are advantaged because they already practice in

public space and handle large projects and budgets.

(but

sometimes I wondered if it wouldn't be more effective as something discreet

that spread over a large area or suburb. Why was large and significant

important? )

It

seems I was chasing the opportunity to do a big commission, which was outside

of a school, but which included community members as makers. Could I transfer

my usual practice of working with communities inside schools, to public places

outside of schools? Could community involvement in making be a part of a large

permanent public art commission?

Now

of course my problem was how to get the work I did with people into a larger

form or to have it recognised as a good way of working. I felt that I needed to

convince people somehow. But who were they? and what did they do? And how to

get around them or convince them? Or alternatively, how did other people do

this work? How did other projects evolve and happen in public space which

involved community members in the making.

The philosophy of community participation is constrained,

altered and shaped by the practical needs of time, organisation, and the need

to be aesthetic.

The physical

I

believe that the physical act of making is important and also choice is

important. I think there is a difference between consultation and participation

and there are different depths of participation. Consultation is dialogue,

participation could be in designing, talking about what needs to be included,

but making connects the mind and the hand. People can suggest ideas or speak or

write but that actually making and manipulating materials that are directly

used in the artwork is a significant act. And having choices so that they are

designing and making using their minds, making choices and using their hands to

make the work are very meaningful processes. When I work with community members,

they have to act on the material. Making the artwork with their hands creates a

direct relationship between the people and the artwork. Consultation and

participation in design means that their intellectual ideas might or might not

be used, but if you are involved in making the artwork it has your stamp of

individuality of choice on it. It is marked by you and your hand. It has your

fingerprints on it. The creative work emerges from the ideas in your head,

through your hands and into the artwork. When I photographed the involvement of

people in making the work, I often photographed their hands, I also looked for

actions of the hands, for example manipulating the clay, using tools and

painting the artwork. There was the artwork but if the hand was in the photo it

emphasised that a person was making the artwork. This was the connection

between the person’s ideas and the artwork. The hands did the work. When it is

a finished artwork in public space people like to touch the work in order to

connect with it.

This physical relationship to the artwork

paved the way for an emotional connection.

This affects the artist who often carries,

processes and installs the artwork.

And likewise, the community members who

physically participate in making the work spending their voluntary time, energy

and intellectual thought in making it may also develop this emotional

connection.

craft

Although aesthetics are partially

sacrificed for participation, the use of an crafts-person assists with making a

work that gives pleasure to the audience of passers-by and also the makers. Aesthetics

is a really important part of the work. It doesn’t necessarily have to be

beautiful but it has to engage the audience without repelling them. Similarly

aesthetics has to take us on the journey from meeting with the object to

understanding it in some way so that we can connect with it. Craft assists with

this. Craft is the method of getting the material to work successfully both

physically and aesthetically.

Permanent public artwork is bound up with

the particular physical material that makes it permanent, and it has to either

engage a craft of hand-making or otherwise it involves technological

production. The crafting of materials in permanent public art is important

because it is the material that makes it permanent. The artist can’t rock up

and say ‘I’ve changed my mind, tissue paper would embody this idea better’.

The use of craft is also limiting. I found

it difficult to move into abstraction, because I employed the materials to

communicate. My experience was that figurative work or text both able to

communicate clearly were favoured as devices for communicating through the

artwork. It is difficult to offer people abstract or conceptual designs because

they are particular visual languages that not everybody understands.

One way that public

art is practiced similarly to an artists studio practice is illegally or as

intervention. Craftivism, graffiti and street art are art practices in public

space because they are usually part of a repetitive, trialled and developed

practice of making in public space. The

opportunity to develop work by practice is available in these forms simply

because they do not conform to the general requirements of commissioned public

art. They do not consider the stakeholders, the need to be permanent,

aesthetics that will please everyone or social and cultural mores of public

space.

There

are many players in the world of art in public space and public artwork, involved

in works both permanent and not permanent. Players might include; politicians,

commissioners of public art, arts organisations, council arts and urban design

officers, commissioners, architects, planners, owners of large buildings and

gardens, artists, community artists, street artists, graffiti artists, taggers

and lone wolves. These players regularly use public space to express themselves

or their idea of what should be placed in public space. There is a world of

public art with different layers of public art practices and subcultures. And

though they operate in their own genres, they are all part of an intermeshed

world. The hierarchy of power could be imagined to have the players with money,

government and the law behind them, at the top of the pile.

But each player in this game has their own weapons or tools in how they might gain space and permanency (or time) in public space. The weapons might be money, skills, tenacity, materials, community acquisence, acceptance, beauty, politics, and more complex things such as fame and the idea of wealth and well-being.

But each player in this game has their own weapons or tools in how they might gain space and permanency (or time) in public space. The weapons might be money, skills, tenacity, materials, community acquisence, acceptance, beauty, politics, and more complex things such as fame and the idea of wealth and well-being.

I thought that the graffiti movement and

all that it had entailed – laws being developed which regulated marking public

space - had affected the other genres, such as community art and public art

commissions. From what I could see, no-one discussed the world of art in public

space as a whole, instead things were discussed in terms of the separate

worlds. Separate worlds were continually being challenged by characters such as

Banksy who crossed easily from one world to the other, by street artists who

were commissioned to make permanent and paid murals, by community artworks that

became permanent, by a commissioned piece of permanent public art being tagged

or altered or by community artworks being written into academic literature. The

interaction of street art, graffiti and participatory art are changing the way

that art in public space is commissioned, viewed and categorised. These genres

make visible different ways of thinking about art in public space and provoke

debate and argument about its role.

I

visualise this world as a Venn diagram, but a complex moving one where the

jostling spheres merged into one another repeatedly. The spheres could be still

or spinning and at different times they showed different faces of the

genre. They all shared the same public

space and battled for attention but often acted as if they were the only ones

there. The whole thing was elastic and changing because of the crossovers and

movements between the genres. For example I felt the graffiti movement had

altered the way in which people saw public space as not a place for anyone to

make their mark on. As a place that needed to be regulated to protect private

property and the way that things looked. We had retracted from thinking of it

as ours because we didn't want it to be everyone’s to do with as they wished.

The taggers had provoked fear. So rules had been made to prevent tagging and these

rules had influenced the way we viewed anybody altering public space. If the

taggers shouldn’t be doing it, then neither should any individual. We had to

categorise and discuss the differences between what is art and what is not.

What is allowed to be in public space and what is discouraged and prevented.

The rules were getting very tangled when graffiti artists entered the museums

or were paid to install permanent murals.

When you place an artwork

in public space the way that graffiti might affect it is taken into account by

the planners and also the audience. I found it startling when doing one mural

which was in a public thoroughfare, that at least half of the people who commented

began their sentences with ‘I hope it doesn’t get graffitied.’ This scenario

has repeated itself in many places and the reality is that it rarely happens

but it points to the interaction between the two genres and that when people

think about art in public space, they have to contend with the uncommissioned

world of public art.

Graffiti and permanent public commissions can seem oppositional, one is permissioned, the other not, but in another sense they both have prominent places in our understanding of visual public space. Graffiti has influenced public art commissions in that plans for how to prevent them being graffitied has become one of the considerations of the commissioning and making process. And sometimes what we think of graffiti suddenly becomes commissioned permanent public art. The object of its fear encompasses it.

If graffiti art is ephemeral and illegal by nature, what happens when we make a permanent permissioned one?

Could we make a permanent public artwork form a material that decomposes?

Could we use a big public art commission, to produce a process-based artwork without designating what the final artwork will look like?

Could we take more risks in processes that might produce something politically incorrect yet be a more authentic expression of culture?

Street art

I began practicing street

art about five years ago. I have a street art practice. The reason it enters

here is that whilst I don’t intend to discuss it, I feel that it has an

intimate relationship with art in public space. It affects and interacts on the

other genres of art in public space. I became interested in un-commissioned

artwork in public space as a method of having an art practice in public space

and also as a vehicle to learn more about other aspects of public art practice

such as materials, ownership and authority to do art and audience reaction.

(below: this could be a

drawing)

aspects of both street

art and commissioned permanent public art

street art permanent public art

usually small due to cost. apart from murals is hardly ever discreet and small

( challenge, make some large street art)

is often a series of small things is usually one big thing

free usually paid for by somebody or some organisation

not owned by anybody owned by a council, or landowner

not preserved protected until deaccessioned

what they both share

both regarded as art

both are made for an audience

both have creators or artists

both are expressions of culture.

they usually take up physical space'

both can be an eyesore.

they won't please everyone

street art permanent public art

usually small due to cost. apart from murals is hardly ever discreet and small

( challenge, make some large street art)

is often a series of small things is usually one big thing

free usually paid for by somebody or some organisation

not owned by anybody owned by a council, or landowner

not preserved protected until deaccessioned

what they both share

both regarded as art

both are made for an audience

both have creators or artists

both are expressions of culture.

they usually take up physical space'

both can be an eyesore.

they won't please everyone

--------------------------------------

Community art:

Perhaps it was a romantic notion I had but I felt that we had drastically moved

away from the seventies and the community arts movement, particularly in the

ways people used public space and used it as if it was their right. It was as

though what was unpolitical, but therapeutic about the movement had been placed

into a nice hand-woven basket called community art and the rest abandoned. But

community art and permanent public art seemed were poles away from each other

and rarely met. But they did so in my art practice.

I feel that community participation in making permanent

public artworks has something very important to say but wasn’t being taken

seriously. It kept being dropped into the bucket of community art and sort of

drowned in it. I think it is a discursive issue, it has to do with how things

are defined and described and perhaps the past roles that public art has

played. I was really

irritated by the community arts bucket. Community

arts seemed to be some welfare and community based practice that went on with

the needy but also anytime you involved the community in something, even if it

had nothing to do with welfare or need, it just plopped straight into the

community arts bucket. ‘oh you involved people, so it’s not real art’. It’s

very nice and it belongs in the field of community art. The art process that I

use is not meant to be therapeutic or make life better for the participant.

They are not lacking in something that art will 'fix'. I am interested in

community participation as a means of making authentic and in depth cultural

expression where the locals or a particular group of community work together to

make the artwork, instead of the sole artist interpreting and reproducing a

singular interpretation of meaning. I am mainly thinking about the

possibilities of what that permanent public art object could be if community

were involved with making it.

The bind of community engaged art is that as soon as the artist allows other persons as makers, it is no longer considered a serious artwork. This is because artists been conjured up culturally, as having some magic, genius or gift needed to create real art. I reject this idea. I believe that anyone can be an artist and that we all have the capacity to say something meaningful through art.

The

crux was that I wanted the people to be valued for their input as the artists

and for the artwork to be seen as a valid expression and conglomeration of more

than one person who had something valuable to say. They were not information or

material but makers of meaning. I was their

conduit who facilitated them being artists and taking up public space

physically and philosophically with their ideas.

One of the things I love about making public art with communities is working

with people. Particularly when they get the opportunity to make something that

goes into public space. It’s a very powerful medium. My role is to facilitate

this process, and in doing so I usually teach them something about the context

of the artwork and the collaboration and of the techniques and materials that

we are using to make. The other thing that happens when you work with people is

that they inevitably teach you something.

Process

The community arts approach places priority on process which might include conversations, research and exploration during which the artwork can deviate from the initial ideas. The artwork is not a clean pre-designed path. At certain stages there will be choices or options for the path to change. It effects the nature of the work and makes it organic. In an artist's individual practice, the process might be important for them but when they place the final object into a gallery or other place to show, the context becomes focused on the object which is the end product of that process. Often the object is placed without any context or (artists statement). Its process and history and context are not shared with the viewer. The viewer is left to make up their own mind about what that object means. Process and outcome, two important parts of any creative activity, are emphasized in different ways in community engaged art, and the process is given an equal footing in the work.

The community arts approach places priority on process which might include conversations, research and exploration during which the artwork can deviate from the initial ideas. The artwork is not a clean pre-designed path. At certain stages there will be choices or options for the path to change. It effects the nature of the work and makes it organic. In an artist's individual practice, the process might be important for them but when they place the final object into a gallery or other place to show, the context becomes focused on the object which is the end product of that process. Often the object is placed without any context or (artists statement). Its process and history and context are not shared with the viewer. The viewer is left to make up their own mind about what that object means. Process and outcome, two important parts of any creative activity, are emphasized in different ways in community engaged art, and the process is given an equal footing in the work.

In large public art commissions the process is designed before the artwork is commissioned. When large amounts of money are involved, the stakeholders need to know what the outcome will be. This makes the practice more object-based and the final artwork taking precedence over the process. Commissions entail careful planning and designing what the outcome will look like. Whilst in reality community participation in making the artwork necessitates it evolving organically, without being planned.

Choice / aesthetic

In collaborative artworks we are all bound by rules and expectations. Not only the artist but also the community member is directed to do something, towards an overall plan. And sometimes, when it is a school project, there is an unsaid rule that they must do the work. But within the making, they also have choices which involve them making the artwork or story their own. This means that the interpretation is coloured by how they respond with their making. The artwork changes and becomes driven with how the community participants respond to the brief.

When people make an artwork together, the outcome is often a mix of disparate parts, it is not one carefully designed image but instead broken up into individual works which are then combined. An amalgam of voices and ideas and aesthetics. The two opponents - individuality and collaboration - clash together, which is great! We get within the artwork the clarity of differences and the evidence that people worked together to make the work.

In collaborative artworks we are all bound by rules and expectations. Not only the artist but also the community member is directed to do something, towards an overall plan. And sometimes, when it is a school project, there is an unsaid rule that they must do the work. But within the making, they also have choices which involve them making the artwork or story their own. This means that the interpretation is coloured by how they respond with their making. The artwork changes and becomes driven with how the community participants respond to the brief.

When people make an artwork together, the outcome is often a mix of disparate parts, it is not one carefully designed image but instead broken up into individual works which are then combined. An amalgam of voices and ideas and aesthetics. The two opponents - individuality and collaboration - clash together, which is great! We get within the artwork the clarity of differences and the evidence that people worked together to make the work.

Aesthetics plays an important role in public art. The more

permanent the work will be, the more importance will be placed on its aesthetic

appeal. If the multitude pay for it then perhaps then the multitude must be

able to appreciate its aesthetic and have some rapport with the work. Aesthetic

is also style which changes over time. Thus you recognize that some public

artworks are of a particular style or era, using materials in a particular way

and you might be attracted to or repelled by. Aesthetic is not an objective thing, it is

often culturally formed, so it’s very difficult to argue that anything is

aesthetic.

Of course the other side of this is that there is a particular aesthetic that people generally enjoy and that is figurative work. I do a lot of figurative work with communities because everyone can understand what the artwork is about and also, they recognise it and enjoy it. I believe that recognition is important to the audience. They need to be able to see what it’s all about to in order to connect with it, and not be separated from the artwork because they can't get a handle on it. This of course creates a particular type of style and aesthetic.

Of course the other side of this is that there is a particular aesthetic that people generally enjoy and that is figurative work. I do a lot of figurative work with communities because everyone can understand what the artwork is about and also, they recognise it and enjoy it. I believe that recognition is important to the audience. They need to be able to see what it’s all about to in order to connect with it, and not be separated from the artwork because they can't get a handle on it. This of course creates a particular type of style and aesthetic.

When I am commissioned to do a project, it has to be discussed, then designed, then the design and quote are delivered and when that is accepted the work must be made according to that plan. I keep the sketches minimal to allow for a bit of development as the project goes along, but in this type of work, the artwork must please. It is imperative that the meaning is well understood, otherwise it does not go ahead.

The end of the work

An experience I continue to have is that at the end of the artwork I have fallen out of love with it. The artworks often take such a physical and mental toll and are a long journey to complete. I have time to think, this would have been better in a different colour or if I had been more careful with this part of the design, or had I done this particular bit which I thought about but didn’t do because if time allowances. If only I had gone the extra mile in that bit there, taken time and care here or foreseen this problem.

An experience I continue to have is that at the end of the artwork I have fallen out of love with it. The artworks often take such a physical and mental toll and are a long journey to complete. I have time to think, this would have been better in a different colour or if I had been more careful with this part of the design, or had I done this particular bit which I thought about but didn’t do because if time allowances. If only I had gone the extra mile in that bit there, taken time and care here or foreseen this problem.

As I leave the artwork I

no longer love it. It is one in a series of developments and what’s in my head

now is the next one which seeks to improve on the past one. I walk away

and onto the next artworks. But time and feedback redevelop the meaning of the

artwork for me and retrospection will place it somewhere in the history of my

art practice. I care for its longevity and wellbeing (and unfortunately because

it is part of my resume, inextricably links to my career and success) and if it

lasts longer the audience will be greater and it will be more worthwhile.

After

a permanent public artwork is situated in space for a few years it has a new

value and definition which has evolved from the people who see it on a regular

basis. How the locals feel about the artwork and what meaning it derives for

them changes over time and no matter what the intentioned meaning of the

artwork was, it will become a different meaning and importance for the

community.

No comments:

Post a Comment